COMPARATIVE RELIGIONS 101

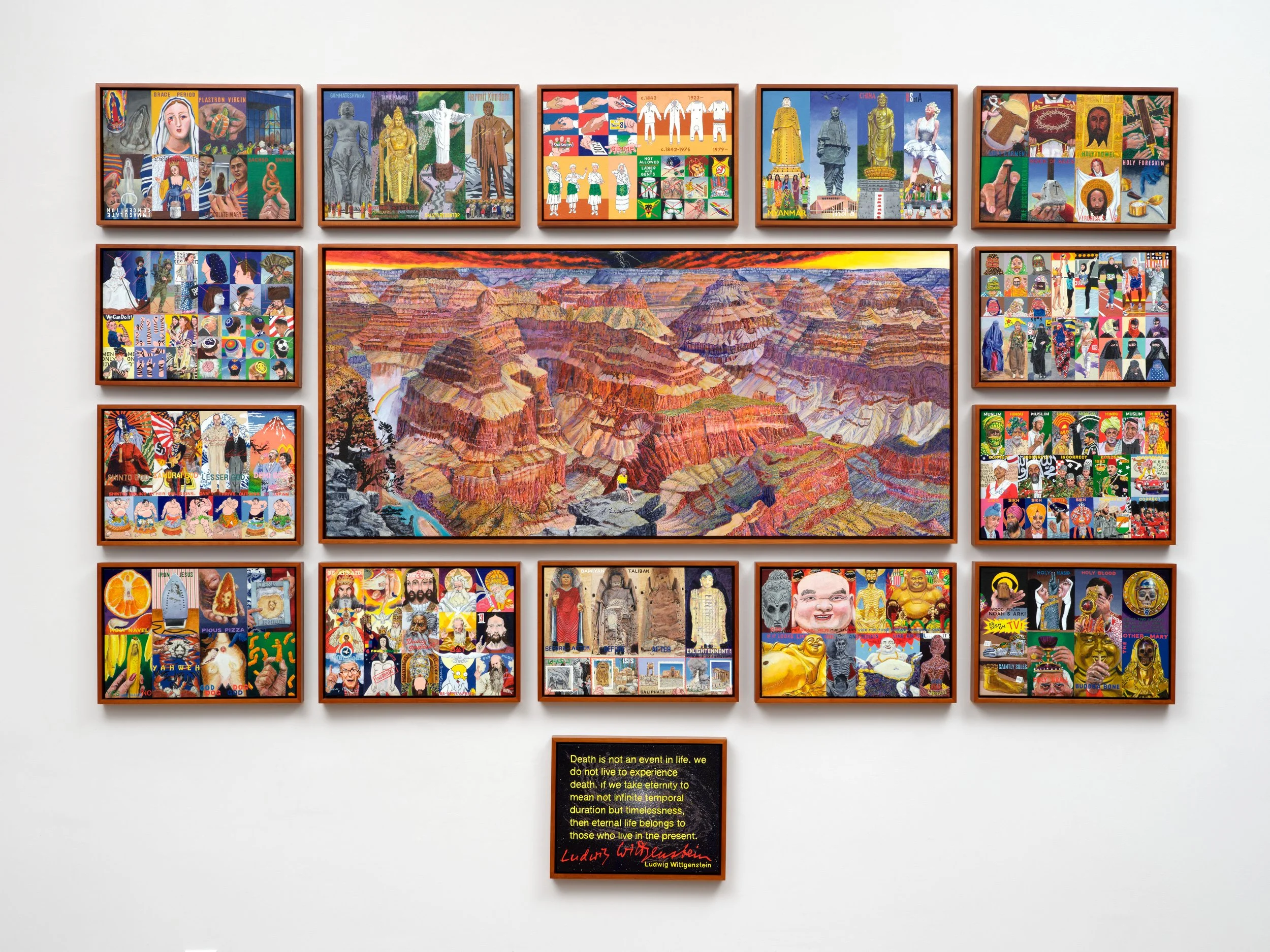

Comparative Religions 101 - 2014/2019 - acrylic on canvas (16 panels) / 11" X 16" / 11” x 14” / 24" X 53" / (Installed) 53" x 91"

¡SELECTED THEN REJECTED!

EXHIBITION RECORD - COMPARATIVE RELIGIONS 101

2022 TIMELINE : JANUARY 12 - SEPTEMBER 12

JANUARY

JANUARY 12, 2022 - SAKOGUCHI IS INVITED TO BE ONE OF THE PARTICIPATING ARTISTS IN THE ORANGE COUNTY MUSEUM OF ART’S CALIFORNIA BIENNIAL, SCHEDULED FOR FALL OF 2022

JUNE

•JUNE 24 - sakoguchi IS NOTIFIED THAT THE ORANGE COUNTY MUSEUM OF ART HAS SELECTED COMPARATIVE RELIGIONS 101 FOR INCLUSION IN its exhibition “California Biennial 2022: Pacific Gold” OPENING OCTOBER 8, 2022

AUGUST

•AUGUST 2 - sakoguchi receives loan form from Ocma; and it is SIGNED and sent BACK to THE museum on August 10

•AUGUST 18 - PACKING OF COMPARATIVE RELIGIONS 101 FOR PICKUP IS NEARLY COMPLETE

•AUGUST 19 - sakoguchi LEARNS THAT QUESTIONS HAVE BEEN RAISED ABOUT CONTENT OF COMPARATIVE RELIGIONS 101, BY OCMA EDUCATION DEPARTMENT

•AUGUST 24 - OCMA IS INTERESTED IN RECEIVING VIDEO/AUDIO OF THE ARTIST SPEAKING ABOUT COMPARATIVE RELIGIONS 101; AND THE MUSEUM WILL SEND SOME WRITTEN QUESTIONS

• AUGUST 25 - sakoguchi BEGINS TO TAKE DAILY TIME OUT FROM CURRENT PAINTING PROJECT, TO RECORD AUDIO FOR OCMA; AND HE RECEIVES A LIST OF 17 QUESTIONS FROM THE MUSEUM

SEPTEMBER

• SEPTEMBER 1 - SEPTEMBER 9 - sakoguchi CONTINUES TO DEVOTE TIME EACH DAY RECORDING THOUGHTS ABOUT COMPARATIVE RELIGIONS 101 FOR THE MUSEUM, WITH OCMA’S LIST OF QUESTIONS IN MIND

• SEPTEMBER 4 - AN ARTICLE ABOUT “California Biennial 2022: Pacific Gold” APPEARS IN la times, With specific mention of COMPARATIVE RELIGIONS 101

• SEPTEMBER 6 - sakoguchi DECIDES TO ADDRESS OCMA’S LIST OF QUESTIONS IN WRITING; AND ALSO TO PROVIDE THE MUSEUM WITH A SERIES OF TEACHING-AID VIDEO “SLIDESHOWS” THAT SPEAK IN DETAIL ABOUT COMPARATIVE RELIGIONS 101

• SEPTEMBER 8 - ORGANIZING IMAGES AND sakoguchi’S RECORDED THOUGHTS FOR “SLIDESHOWS” BEGINS

• SEPTEMBER 9 - sakoguchi’S WRITTEN RESPONSE TO QUESTIONS IS GIVEN TO OCMA

• SEPTEMBER 10-12 - FULL-TIME EDITING OF “SLIdeshows” continues

REJECTED:

• SEPTEMBER 12, 2022 - ¡REJECTED! - SAKOGUCHI IS NOTIFIED THAT OCMA WILL NO LONGER INCLUDE COMPARATIVE RELIGIONS 101 IN “CALIFORNIA BIENNIAL 2022: PACIFIC GOLD” BECAUSE THE MUSEUM WILL NOT SHOW ANY WORK THAT DEPICTS A SWASTIKA

OCMA QUESTIONS - BEN SAKOGUCHI

1. How do you see your work in relationship to political satire and caricature? Do you consider yourself a satirist?

I don’t usually characterize myself, but I do employ satire, and especially irony, in much of my work—once described as “very serious and very funny.”

2. Your work combines different aesthetic forms of presentation from commercial signage and advertising, history painting, printmaking, through to Pop Art and cartoons – can you share more about your approach to painting and how you see the form in relation to the content you are exploring?

While I’ve used printmaking, assemblage, and installation in the past, I’ve found painting to be the best fit for me as I put my ideas into visual form. I’m open to appropriating images from any source, to re-combine, and sometimes modify, as suits my purposes.

3. What do you hope audiences take from your work?

My highest hope for my work is that the viewer is motivated to think...and to question.

4. Can you talk more in-depth about where the imagery in the work comes from and your relationship to the media?

5. How much of your imagery is pulled from the news, television, and/or the internet?

For over seventy years, I’ve been a voracious collector of images and information from any media I’ve had access to. Early on, it was comics, magazines, books, newspapers; later, television; and in recent years the internet has dramatically broadened the available selection. The more topical the theme of a particular work, the more likely that the imagery will have been sourced from the news—and even historical images may come from the internet.

6. How important is it for educators to speak to the original source material when talking with audiences about the work?

I think it may be important to impress upon the audience that virtually all the imagery has been painted from media sources; and that while in most cases a fairly direct representation, artistic license cannot be ruled out. But since these canvases are pieces of visual art—and not journalism or scholarly writing—there are no footnotes that credit sources. And it is okay for the viewer to be left wondering about the original source material.

7. What influences your selection of imagery? Do you collect images or build an archive from which you pull from as you work?

Image selection evolves as the work takes shape. I’m constantly adding to a large archive, and with the internet my main source of new images these days, I also keep researching a subject as I’m painting it.

8. In some of the pieces you explore the dichotomy of the binary positing the terms “correct” and “incorrect” as one example. Can you expand on your use of this as a strategy/structure/frame?

Having been victimized by binary thinking at a very young age (when my family was incarcerated on the basis of ethnicity during World War II) I’ve long had a heightened awareness, and do sometimes focus on it in my work. “Correct” and “Incorrect” is a device I’ve been using for many years now, in some instances with more humor than in others, but always bearing in mind how very subjective humor itself is.

9. Your work sometimes incorporates xenophobic, violent, and racist symbols, imagery, and language as part of its compositions. What are your thoughts on the current discourse around how the reproduction or continued representation of this imagery and language contributes to continued violence, harm and/or negative stereotypes?

I’ve been on the receiving end of xenophobia and racism for most of my existence, and have lived though a long period of time where continued violence, harm and negative stereotypes were widely tolerated and swept under the rug. I favor selectively shining a light on the offending symbols, imagery, and language, both past and present, as a reminder of our history and of how far we still have to go as a society...and of how vigilant we need to be.

10. Taking the work Comparative Religions 101 (2014/2019) as an example, what are your critical or artistic methods to engage the cultural and religious imagery and symbols without reinforcing stereotypes and negative sentiments toward religious communities?

In college, sixty-five years ago, I was taught that “fine art” should NOT be political. It took me 10 years to unlearn this highly political concept, and another five to fully embrace using political subject matter in my work. Religion has for centuries been a dominant force in world politics: empires, monarchies, nation-states, alliances, wars, crusades, colonization, genocides—all in the name of one church or another. And today, in a country that purports to guarantee freedom of religion, we have political leaders advocating for a theocratic America; and a Supreme Court handing down a decision that imposes the beliefs of one particular religion on the entire population.

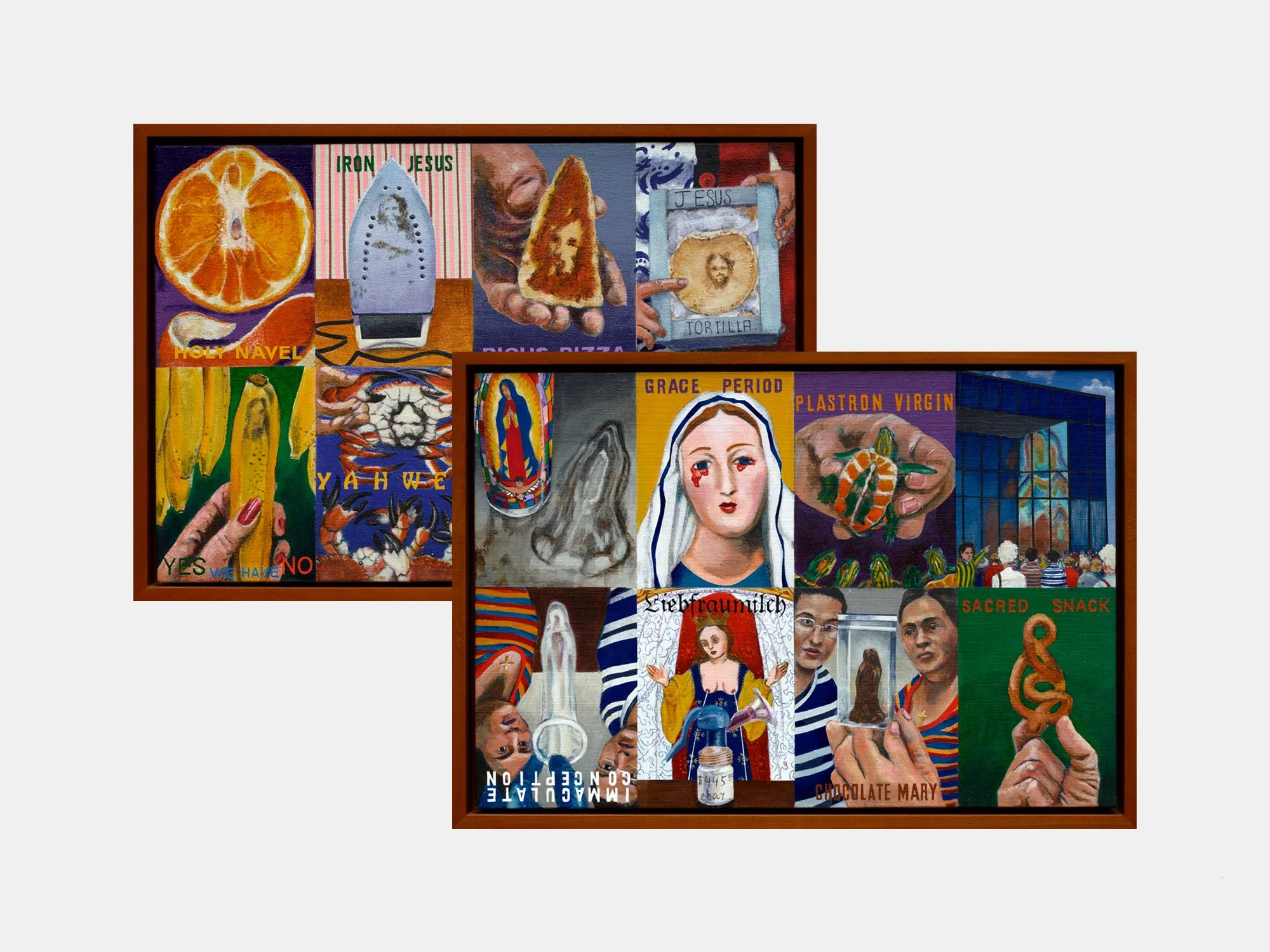

So I approach religion, just as I often approach other areas of politics, by holding up a mirror. And one obvious way to make comparisons among, and within, various religions in a “fine art” format is through artifacts. That is, human-made objects (relics, statues, clothing, etc). I’ve selected artifacts that I, as an outside observer, find interesting or peculiar. And artifacts that seem to contradict a particular religion’s core tenets. Or that illustrate the very human ability to create “workarounds” when the rules imposed become overly restrictive, and still maintain faith in a theology. As a working artist it’s fascinating to me how hard it is for humans to embrace a theological concept without adding Art; and how often the artifacts are imbued with sacred power.

My experience makes me skeptical that Comparative Religions 101, this artifact I have painted and assembled, is likely to have much influence, either way, on a viewer who brings stereotypes and negative sentiments toward religious communities into the museum.

11. Some of the visual elements and language in your work can be read as provocative and even inflammatory for the general public. How might you advise the museum to address an audience member who is uncomfortable, upset, triggered, or angry as a reaction to some of the language and/or imagery in your work?

I have no advice for the museum in that regard. I’ve never believed my role as an artist was to make work that ensured comfort. My paintings are purposefully subject to alternate interpretations, and a reading of Comparative Religions 101 that provokes anger is certainly possible if the viewer is a literalist. But I can’t explain the humor and irony in the work to a literalist, any more than I can explain Red to a person who is (red/green) colorblind.

12. For large panel works like Comparative Religions 101 (2014/2019) and Towers (2014), do you sketch or plan them out before you begin?

I don’t make sketches for any of my paintings, and usually just start with a kernel of an idea, and proceed organically. All the multi-canvas pieces with the same format as Comparative Religions 101 and Towers, began with the large central painting, and then moved on to the surrounding small canvases.

13. How do you determine when a paneled work or a series is complete?

A paneled work is complete when I arrange it on a wall and make a judgement that it “works.” A series is never complete.

14. Have you shown Comparative Religions 101 before? If so, what was the context? Would you share anything about the reception of the work as you understand it?

This is the first time Comparative Religions 101 has been exhibited.

The only recollection I have of my work being received with loudly expressed anger by a member of the public, was during the AIDS crisis in the 1990’s. The offending painting was entitled “Condom Brand.” This was around the time that an artist friend had her minimalist piece defaced by an unhappy viewer at LACMA. And the first director at the Brand Art Center told me of an incident where someone who didn’t like an abstract painting felt entitled to go ahead and write on the surface; while another director at the Brand has more recently said that they’ve come to expect problems if they exhibit work that includes the nude human figure.

“Condom Brand” depicted a uniformed nurse holding a condom, taken straight from a media source.

The Wikipedia entry for “Virgin in a Condom” reads: Virgin in a Condom is a controversial sculpture created by Tania Kovats in 1994. It is a three-inch statue of the Virgin Mary covered by a transparent condom.[1] It was stolen from the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney, Australia within days of being exhibited.[2] It attracted Christian protesters when it was on display in 1998 at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.[1]

The second time I’ve used a condom as subject matter in a painting, is in Comparative Religions 101—on a canvas depicting apparitions of the Virgin Mary, both sincere and contrived. In a 2022 world where condoms are ubiquitous and part of everyday language, whether this minor element of the work will be singled out as particularly offensive, is an open question, I guess.

15. What was the impetus to create Comparative Religions 101? Has your relationship to the work changed over time?

I came across a photograph of Albert Einstein at the Grand Canyon and wondered what someone with that type of mind, and knowledge about the vastness of the universe, would be thinking as they looked out across that landscape.

When I arranged Comparative Religions 101 on a wall in 2014, it didn’t quite “work” for me, both aesthetically and content-wise. I put it aside, shifted focus to other projects, then revisited it in 2019. After replacing or modifying a number of the small canvases, I made the judgement that the work was complete, and moved on to a different area of interest.

16.. How do you see your relationship to the various communities featured in the work?

In looking at society, I’ve always felt like an outside observer. That’s not to say I’m without biases, but I’m pretty impartial as far as religions are concerned. I had moral, upright, non-religious parents. They wanted us kids to be regular Americans, so they said, “Okay,” when we asked if we could attend the local Baptist Sunday school. There, it was repeatedly emphasized that all non-believers would burn in the fires of hell...for eternity. And because non-believers would include my moral, upright parents, I knew this doctrine couldn’t possibly be correct, so I ended my Baptist affiliation. Since then, my relationship to religious communities has been as a guest at ceremonial occasions of importance to friends and family.

17. Who do you see as being centered in the work? Is there a central message or takeaway that you are envisioning that audiences engage with as part of the piece?

Albert Einstein, whose image is physically near the center of the work, is also thematically central, along with the Grand Canyon. The relationship between the two is intended to illustrate our own insignificance in the natural world, extending beyond the earth into the infinite expanse of the universe. A popular public figure, Einstein was often asked about his personal religious views. His answers were sometimes cryptic, and so varied that he can be characterized as deeply religious, or non-religious, depending on which quote you pick out. My pick would be, “Religion without science is blind.” And current established religions date from a time when human knowledge was limited in scope. Even the founder of fairly-recent Mormonism, Joseph Smith, had never seen the Grand Canyon.

When discussing my artwork, I’ve long held that I have no answers, just questions. I hope that audiences will recognize some of the questions in Comparative Religions 101, and will posit their own, as well.

LOS ANGELES TIMES ARTICLE

SLIDESHOWS

Selections from Ben Sakoguchi’s thoughts regarding Comparative Religions 101 (recorded August 25 - September 9, and edited September 8 - 12, for OCMA Education Department)

Slideshow (5:12) - COMPARATIVE RELIGIONS 101 :

Slideshow (2:14) - ALBERT EINSTEIN AT THE GRAND CANYON :

Slideshow (4:07) - DEPICTIONS OF GOD :

Slideshow (3:17) - DEPICTIONS OF BUDDHA :

Slideshow (3:23) - GIGANTIC STATUES :

Slideshow (10:29) - CLOTHING :

Slideshow (5:08) - RELICS :

Slideshow (5:42) - VISIONS :

Slideshow (5:43) - SHINTO :

Slideshow (3:15) - BAMIYAN BUDDHA :